Political Campaigning in the Age of Coronavirus

BY IQM EDITORS

Up to mid-March 2020, the United States was in the midst of a national and state-wide election cycle that was dominating cable and broadcast news networks. The states of Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina had just held their democratic primaries for the office of U.S. President. Then, practically overnight, political campaigns grinded to a halt due to a public health crisis with the potential to shut down entire nations. It’s name - coronavirus.

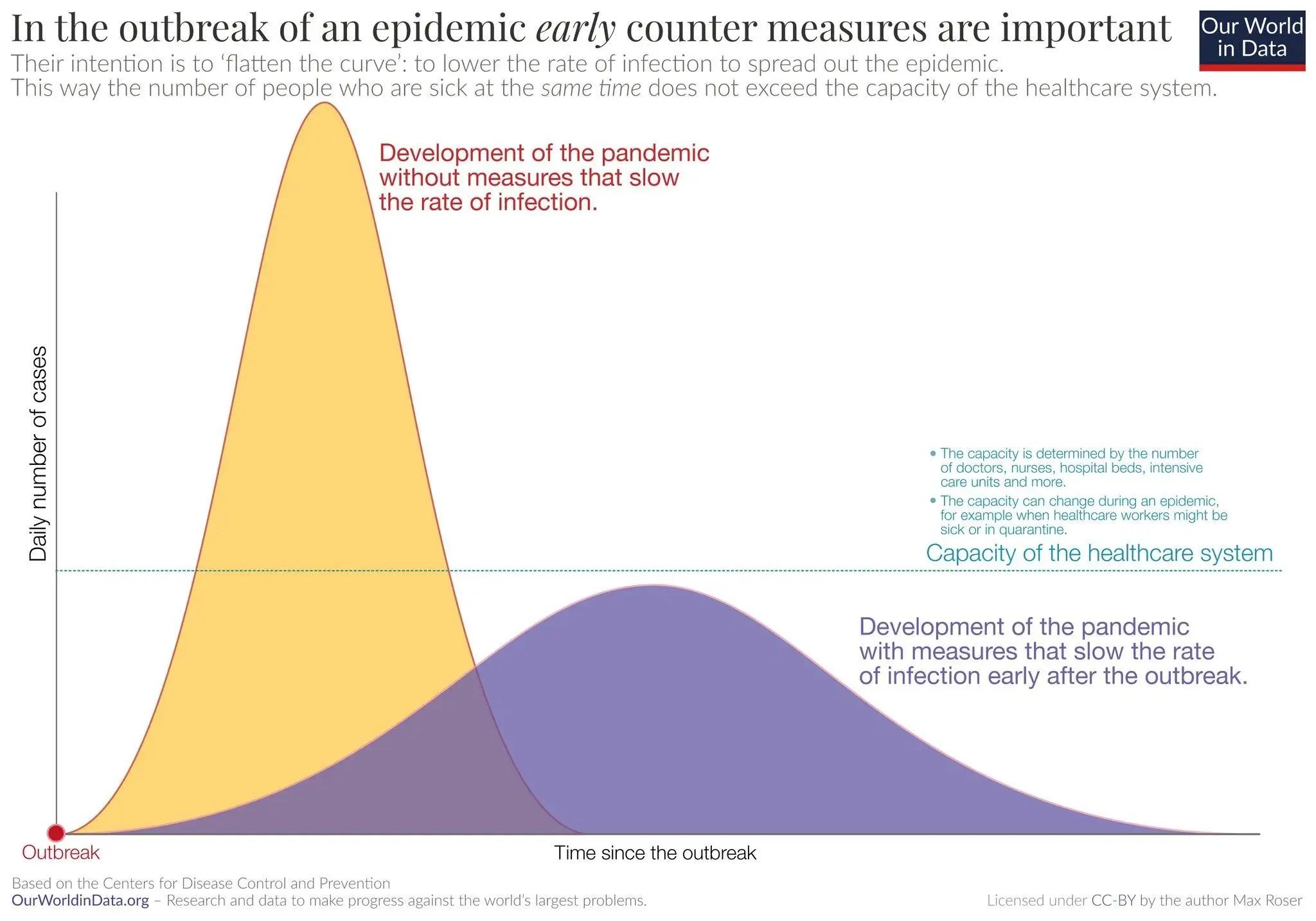

The highly contagious virus is easily spread among populations. The World Health Organization (WHO) quickly declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 and the White House and public health officials scrambled to find ways to flatten the rate of infection curve. Without a vaccine, public health officials have prescribed mitigation measures. Five days after the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, President Trump encouraged Americans to social distance for a period of fifteen days. The administration subsequently extended social distancing guidelines for Americans through April 30. Most U.S. states have forbidden gathering of more than 10 people. They asked their residents to cancel discretionary travel, avoid bars, restaurants, and food courts. In essence, a new coronavirus normal was established with more than ¾ of all Americans under stay at home orders. As the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has exponentially increased, the president hopes that the U.S. will return to a semblance of normalcy by June 1.

The social distancing measures have saved lives, but halted the U.S. economy and political campaigning during an election year. The Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden campaigns for President cancelled large public events out of concern for the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost every candidate and state has followed suit. There are no more political rallies, handshake lines, posing for selfies, or for all intents and purposes, voting at polling sites without significant safeguards. The question to some skeptics has been, are these extreme measures necessary? The IQM data science team took a closer look at the potential impact of the COVID-19 disease on American voters.

COVID-19 Could Disproportionately Impact our Most Likely Voters

The impact of coronavirus will have far reaching impacts on this year’s national election cycle. A CDC report on the COVID-19 disease states, “older adults and people of any age who have serious underlying medical conditions might be at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19.” It continues, those at high-risk for severe illness include:

- People aged 65 years and older

- Other high-risk conditions could include:

- People with chronic lung disease or moderate to severe asthma

- People who have serious heart conditions

- People who are immunocompromised including cancer treatment.

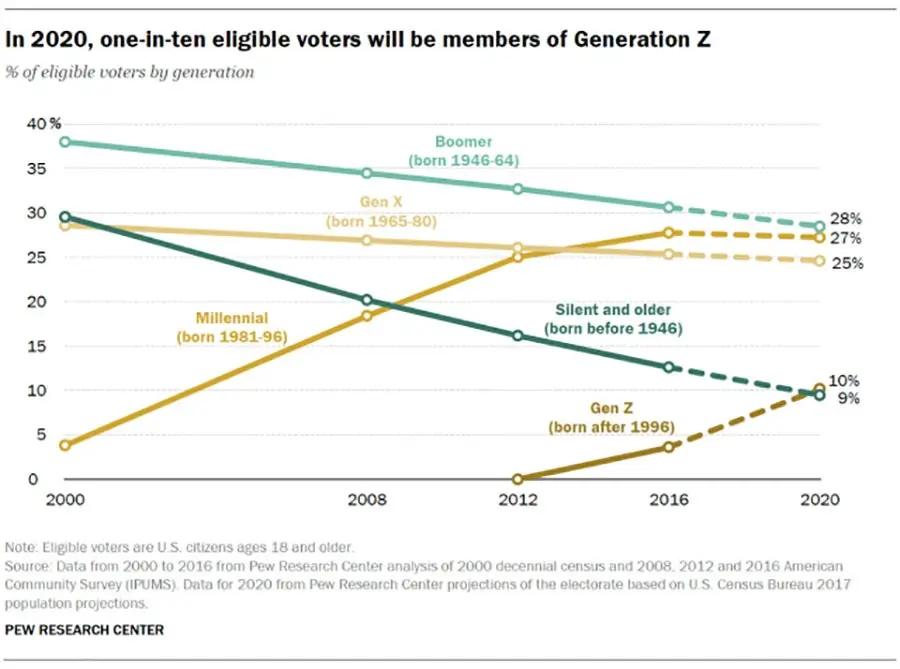

While not exclusive to older Americans, the age groups that are most at risk to this virus are also the country’s most likely voters. According to the Pew Research Center, “in 2020, nearly a quarter of the electorate (23%) will be ages 65 and older, the highest such share since at least 1970.” Plus, the combination of persons aged 65 years+ and Baby Boomers (born from 1946-64) will account for approximately four out of ten eligible voters in 2020. The IQM data team delved deeper into the current outbreak models and found more frightening figures.

Our Methodology

The first step in our process was to identify the most likely voters in the United States. Working with our data partners, IQM utilized an established scoring system assigned to citizens based on frequency of voting. That score, on a scale of 8, represents the total number of even year general and primary elections in which voters have cast a ballot. For example, voters with a score of 6 or higher, voted in at least two U.S. national or state-wide elections over the last four even-numbered years.

Next, we analyzed data on voter’s party affiliation. Voters from unknown age groups were distributed among our data set proportionately. We also combined all voters older than 80 into one 80+ group. Lastly, we assumed a uniform 50 percent infection rate multiplied each age group according to China CDC’s fatality rate of COVID-19.

Our Findings

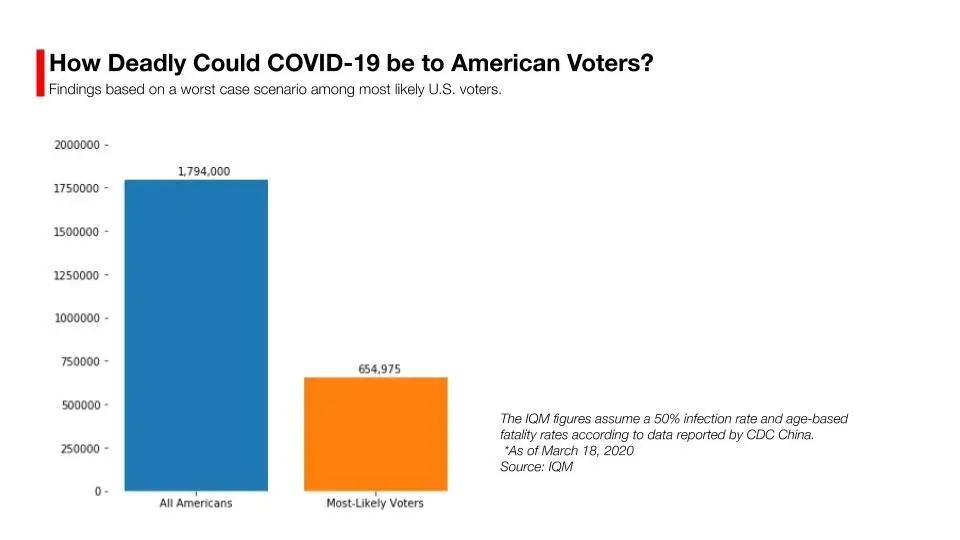

Assuming a 50 percent infection rate, with little to no nationwide mitigation methods, our projection shows nearly 1.8 million Americans could die from the COVID-19 disease. Mitigation measures include national shelter in place orders, closing of schools, and other social distancing policies. The measures also may include nationwide virus testing, improving emergency room readiness, and mobilizing the National Guard to aid in response.

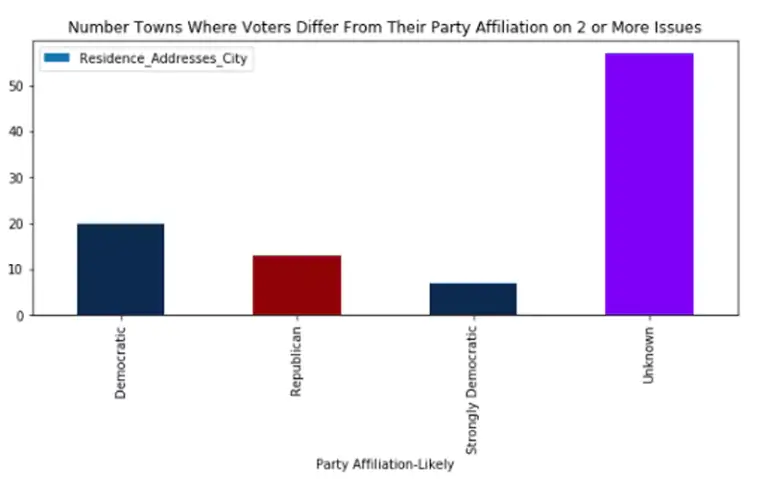

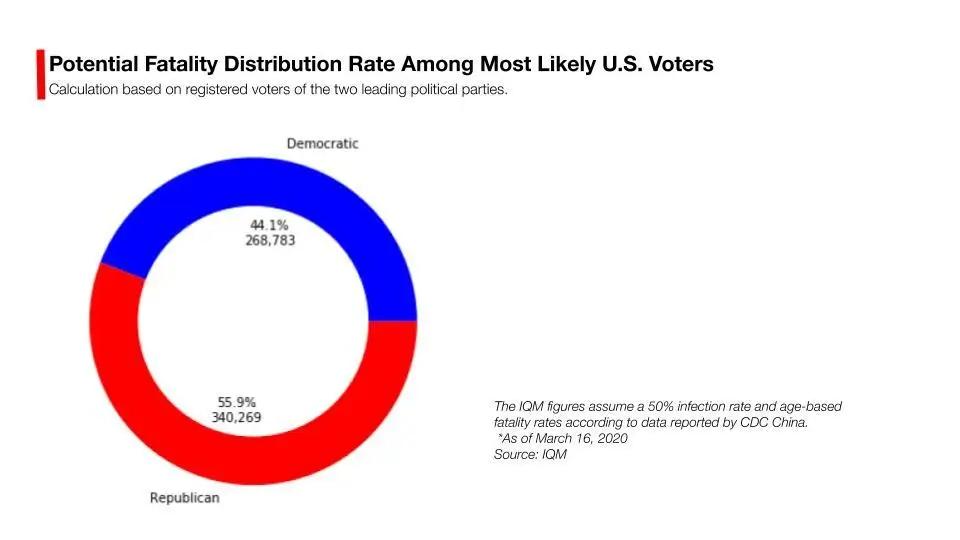

37 percent or nearly 700,000 of those fatalities could be among the nation’s most-likely voters (Chart I). When you break down those numbers among voters who identify with the two major political parties, the fatality distribution rate would be higher among Republicans ≈56%, compared to ≈44% within the Democratic ranks (Chart II). When the 2020 election cycle gets back to normal, the Democratic and Republican National committees could face a completely changed electorate.

The president faced an uphill battle for re-election, which has been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. As recently as April 1, more voters say the White House isn’t doing enough to combat the coronavirus outbreak. A Morning Consult/POLITICO poll found 47 percent of voters feel the administration isn’t doing enough in response to the outbreak. 40 percent feel the administration is doing the right amount.

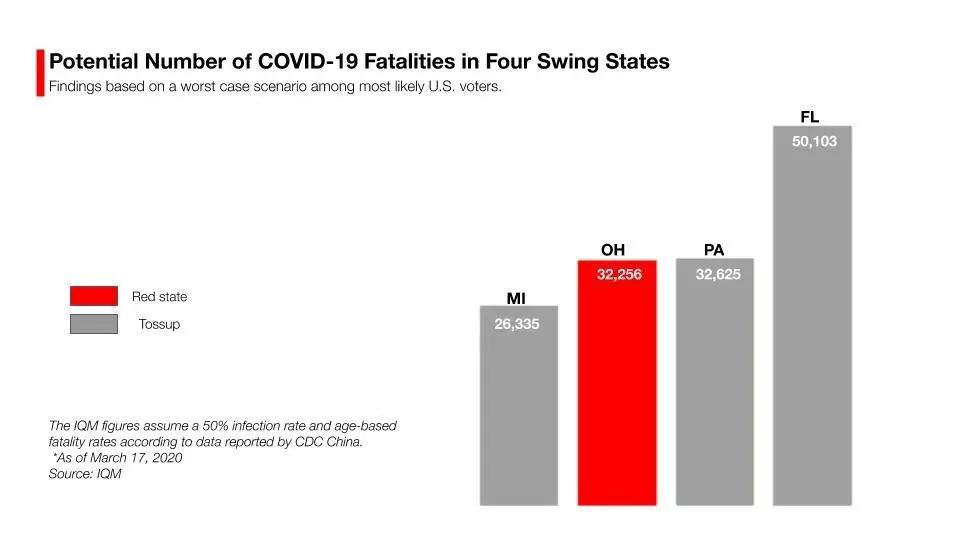

Candidate Trump flipped a number of midwestern states by extremely slim margins. For example, he won Michigan by 0.3 percent, Wisconsin by one percentage point, and Pennsylvania by 1.2 percent over Senator Hillary Clinton. In IQM’s model, Michigan could unfortunately lose over 26,000 lives to COVID-19 (Chart III). President Trump won the state by a mere 13,080 votes. Plus, the Governor Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan has criticized the president’s response to the pandemic. The president in turn, has insulted the popular Governor in interviews and press briefings. The president’s campaign stands to lose 16 electoral votes, if Michigan flips to the Democratic party.

If the loss of life in Pennsylvania follows the IQM model, the narrow Trump victory is in greater jeopardy. Partisan politics and the 2020 election for the office of U.S. President are not as important as the administration’s response to the potential loss of life. But our findings are a sobering reminder that our election systems will be radically changed by this public health crisis.

Chart I.

Chart II.

Chart III.

Where Do Political Campaigns Go From Here?

Public, in-person events are traditionally the lifeblood of political campaigns. For instance, candidate Trump benefited greatly from his battleground state rallies in 2016. The production allowed the campaign to collect data and re-target audiences almost in real-time. Plus, the spectacles garnered free earned media coverage on cable news. Initially the Sanders campaign for President rode the momentum of his public events to a lead in national polls and media coverage during the current 2020 election cycle. But with the onset of COVID-19, all the candidates in national and state-wide elections were left scrambling to restructure their campaigns as the pandemic extended from weeks to months.

FiveThirtyEight wrote in March of this year, “American campaigns and campaign coverage are driven by what historian Daniel Boorstin called “pseudo-events” — artificial inflection points meant to “drive the message.” Rallies are the crown jewel pseudo-events in our age of populist politics.” But with a few of the major state primaries already completed and the highly polarized electorate, the positive impact of in-person events could be a vanity play. A huge crowd could convince a candidate that their campaign is performing well. But without the affirmation from a live crowd, campaigns will need to get more creative to interact with the electorate. These could include virtual town halls, Q&As over social media, more frequent campaign emails to voters, and political ads to help inform and persuade voters.

After the COVID-19 pandemic wanes, it would be intriguing to analyze the impact the stay at home orders had on political fundraising. While most Americans donate less than $100 (Pew Research Center) to a candidate, party, or campaign, big-dollar fundraising is still primarily conducted via face to face interactions.

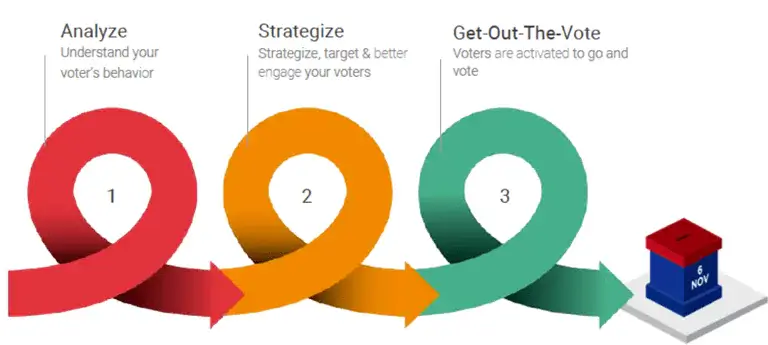

Virtual political campaigns will need reliable voter data and delivery platforms. At the national level, the Trump campaign for President has been applauded for its data collection apparatus and ability to re-target it’s base of voters efficiently. According to an article in the New York Times in March 2020, the Trump campaign has pushed the RNC to adopt new strategies for their data and ground game. The campaign is less reliant on television advertising and created a private company outside of the Republican party to serve as a singular clearinghouse for its voter file. The private nature of the new group provides greater operational flexibility and frees them from the constraints of some campaign-finance laws. The Democratic party has been playing catchup since 2016, but made strides during the 2018 midterm election cycle.

Several startups grew out of the push to digitize voter engagement after 2016. The success of the new players in political ad tech will be their ability to deliver ads instantaneously to a matched and targeted group of voters. Further, those platforms will need to provide greater transparency of their entire ad exchange process, exceed changing KPIs quickly, and best utilize internal human intelligence about the domestic and international political processes.