The Secrets of Your Voter Profile Weren’t So Secret–And It’s Okay

BY IQM EDITORS

The Digital Future of the Voter Roll.

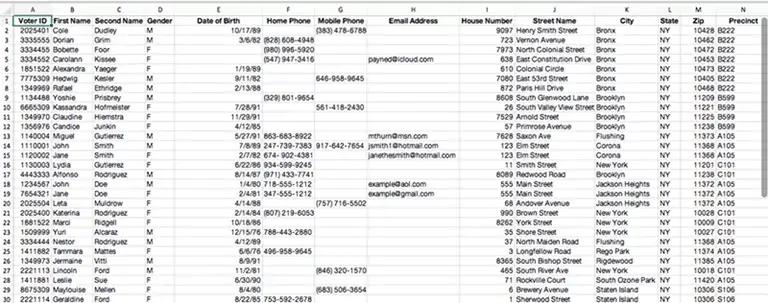

U.S. voters could learn a lot about modern politics by volunteering on a campaign or interacting with their local Board of Elections. A major takeaway would be the lack of sophistication of the standard voter file. The file is, in essence, basic voter information in a spreadsheet or database that can be purchased by political campaigns. In most states, the standard voter file consists of only names, addresses, phone numbers, ethnicity, gender, party registration, and voting history.

This lack of sophistication is why modern campaigns have deemed the voter file insufficient to win elections. Campaigns need a more robust, and accurate portrait of who’s voting for them, the issues that matter to them most, and who remains undecided. Furthermore, campaigns need to address the security concerns of US citizens’ outdated version of the voter file. The voter file has evolved but has more growing up to do.

Some states provide campaigns with a spreadsheet that compiles this information in the form of a CD-ROM (if you can believe it).

One of the most pressing issues that our political customers have expressed is that these voter profiles are often left incomplete. They are typically created manually and can contain misspellings, making identifying voters more difficult and creating a lag behind the real-time changes in population. In electioneering, an entire service industry has emerged of consultants, software, and operatives who match voter files for political campaigns.

Even if the files were 100 percent complete and accurate, they were created before email and smartphones became the dominant modes of public media consumption and communication. Could you imagine running any kind of awareness campaign without cell phone numbers or email addresses? This is the reality of local politics.

Even as campaigns mature, they are still using outdated methods of capturing voter information. At public events, political candidates collect data via paper sign-in sheets, while fundraising and donor data is organized separately, creating a multi-step process just to cross-referencing a likely voter, who has donated to the campaign.

Cash-strapped campaigns end up dedicating people and resources to data entry, list maintenance, and updating their digital voter files, just to address the inefficiencies forged via this outdated method of voter information collection.

Voters are Talking, Campaigns Need to Listen

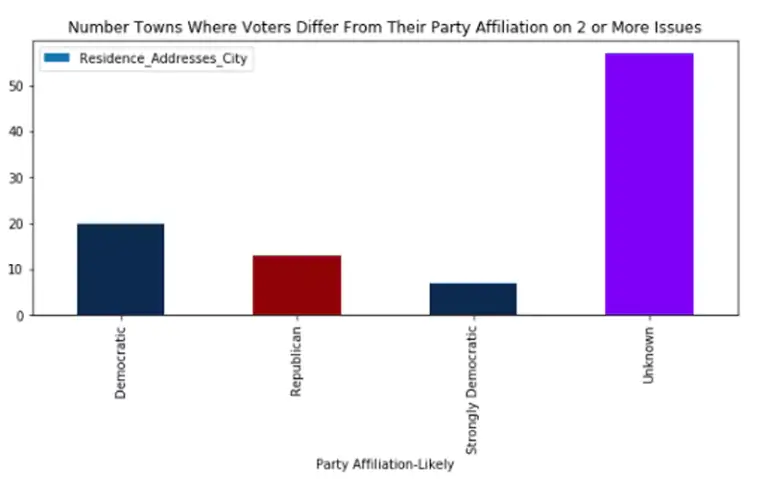

The major shortcoming of the lists still remains–they don’t educate campaigns about what voters care most about. For example, can a spreadsheet tell a campaign worker in a formerly thriving manufacturing center that ‘access to affordable healthcare’ and ‘retaining the workforce’ are major voter concerns? They can’t.

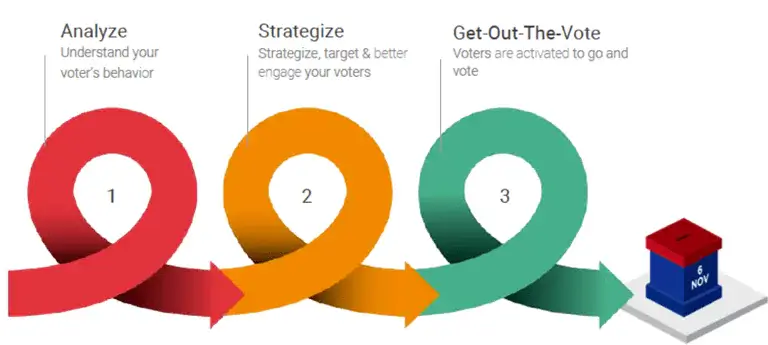

Voters are having those conversations online. The websites they visit, the posts they like on social media, the news articles they share and comment on are all huge indicators of sentiment and the issues that matter most to a community. Campaigns need the mechanisms that collect, share and analyze their information, to listen and understand their voter base. This is where political big data solutions providers step in. Developers, analysts and political operatives have started to work together to collect publicly available information on voter behavior and opinions to build predictive models of targeted voter bases.

Barack Obama’s presidential campaign gets a lot of credit for being the first team to integrate big data best practices with more efficient outreach to undecided voters. So how did they do it? The combination of data collection, algorithms, and statistical breakdowns have created a new way to view a voter base. The MIT Technology Review wrote in 2012, “…analysts thought of voters as individuals and worked to aggregate projections about their opinions and behavior. The electorate could be seen as a collection of individual citizens who could each be measured and assessed on their own terms. Now it was up to a candidate who wanted to lead those people to build a campaign that would interact with them the same way.”

Taylor Valley, a political consultant who worked with NationBuilder, a software solution for campaigns, recalls a story from his days canvassing on a countywide election in 2014. The campaign hired interns who merged the county’s voter file with their relevant social media accounts and found roughly 2,500 matches.

When the candidate was out in the field, he knocked on the door of undecided voters and said, “I noticed that you liked my post on education reform, so I wanted to stop by and let you know that I fully support our teachers.” This “social GOTV” was incredibly successful. More than 80 percent of undecided voters who answered the door responded positively to the candidate’s call to pledge their support on Election Day.

Valley learned that merging data is no easy task. He also noted that this approach assumes that at least 50 percent of legitimate social media followers of a campaign or candidate are constituents in the respective district.

The result of this example was a positive one, where voter data and sentiment was used legally and ethically to form a relationship between the voters and a responsive political candidate. However, when this information is collected illegally or for ill-intent, a voter’s right to privacy can be compromised. For this reason, voters have the right to protect their privacy, by ‘opting out.’

Opting Out

Increasingly, the general public is living online. We communicate, make financial transactions, shop, even find a mate online. But that doesn’t mean we need to reveal everything about yourself on our social media platforms. We have an inherent right to keep our voting behavior private by ensuring the privacy of our identity and personal information in the digital space. And this necessitates a few extra steps.

On social media, you can change the privacy settings of your posts at any time. If you prefer, you can share your political opinions only to specific friends.

Political marketers collect common information found on every communication medium used on the Internet, such as browser type, operating system, browser language, Internet Protocol (IP) address; Internet Service Provider, and mobile advertising identifier, for mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets. You may opt out from tracking and interest-based advertising at any time. Remember, you will need to opt out separately for each browser or device you use.

For more information about how you can successfully ‘opt out,’ visit the resources including the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI), Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA), Digital Advertising Alliance Canada (DAAC), Digital Advertising Alliance EU (EDAA), and the DAA AppChoices page.

Two Reasons You Don’t Want to Opt Out

Without interest-driven advertising, consumers would still see ads on the Internet. However, those ads will likely have nothing to do with the products or services you care about. With interest-based advertising, the content you consume online is tailored to your interests.

Additionally, companies that create websites and apps rely on the revenue from interest-based advertising to support the rich array of content they produce. Without that revenue, the content would either be unavailable, or consumers would have to pay for it.