Politics Ain’t a Game, But Campaigns Are Encouraging Us to Play More

BY IQM EDITORS

Can Political Campaigns Compete in the World of Fortnite?

Courtesy: Adweek

So, why not leverage an industry that dominates our smartphone screens? A 2016 article in Adweek reported that “voters are…playing games more often.” According to comScore data…, the average smartphone user spends 5.5 hours per month playing games—more than he or she spends with Netflix, Snapchat, Twitter or ESPN.

Zynga, the popular game developer behind Farmville and Words With Friends launched native gaming ads in collaboration with The Rubicon Project for the U.S. national elections in 2016 to create SponsorPLAY ads. The ads ran inside of a game’s virtual world while users were playing [think passing by a virtual McDonalds while your avatar is quarrying for rocks, or adding Hidden Valley Ranch on the salad you just picked from your farm]. These ads ran for both brands and political campaigns. The results showed a 51 percent opt-in rate, with 600 percent engagement rate. Now, two years later politically-themed games are gaining even more traction.

While major presidential candidates did not buy ad space on this platform, the availability of this service for political campaigns and the effectiveness of increased engagement rates made advertising on gaming platforms an attractive alternative to video ads.

Cash Rules Everything Around Me, Including the Voting Booth

Courtesy: TBS

Earlier this year, Samantha Bee, the host of “Full Frontal with Samantha Bee” demonstrated the potential for political engagement in gaming after she discovered that 54 percent of her audience was not registered to vote. Shortly after, she launched her own gaming app, called This is Not a Game: The Game. The app was designed to test the electorate’s knowledge. It has an added incentive, cash.

The inaugural $5,000 prize was split among a group of winners. Players who get knocked out could earn second chances by completing challenges like registering to vote and signing up for election day reminders.

Bee told Wired, “I always had a sense of purpose with this game, but this recent finding has really strengthened that resolve; we can do better, for sure,” Bee says of her audience. “Obviously the stakes are very high for civilization as a whole. But we’re not sitting around thinking that we’re going to go out and save democracy, we’re really not. We’re just trying to help in any way we can.”

While the jury is still out on how many unregistered voters of Samantha Bee’s game app users have registered to vote since the app’s launch, the creation of a game has acknowledged that voters are increasingly more active gamers and marketers are seeking creative ways to get voters more invested in national and local politics.

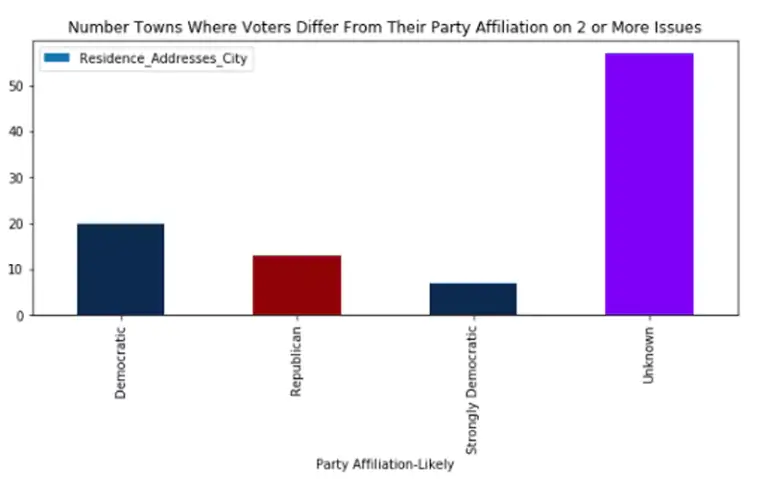

The launch of This is Not a Game, also provided a way for campaigns to capture a snapshot of their audience via direct feedback. In this case, it was the audience’s knowledge level of politics; but campaigns could create quizzes and other interactive mediums to track voter behavior, demographics, and data for improved micro-targeting strategies.

The Game Never Ends

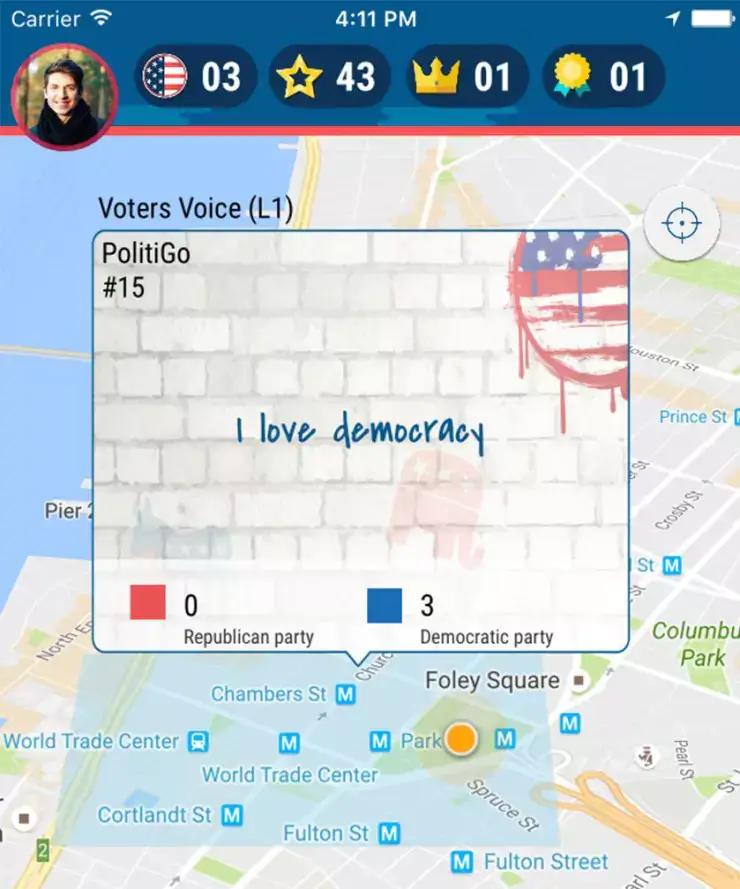

Earlier in its development, IQM experimented with a politically-themed game called PolitiGo. The game was designed to encourage players to make their voices heard, conquer districts for their party, leave virtual graffiti to represent their side, and hear the silliest things virtual candidates had to say on the campaign trail. Gaming, native ads on online platforms, even automated text messages sent to voters’ mobile devices are seeking the same goals. Using technological solutions to increase participation in the political process. Increasingly, winning campaigns are utilizing modern tools in conjunction with grassroots GOTV tactics to win elections.

Courtesy: Screenshot of POLITIGO; Courtesy of IQM

Voters are looking more and more like players in the virtual world of on online and in-app gaming. And young voters, in particular, are frustrated with not seeing immediate results and rewards for performing their civic duties. Gaming engages voters on a daily basis, while instantaneously rewarding their behavior and knowledge. The lasting effects that political campaigns can have on voters could be greatly enhanced by the ubiquity of campaigns’ presence on the platforms which (potential) voters spend the most time.

While the virtual advertisement is still fairly new space in the advertising world, the promise of pervasiveness is impossible to ignore. Political campaigns need to think as open-mindedly as game-developers and ask questions like: Will a 2020 presidential candidate launch their own gaming app? Or, could we possibly see virtual voting booths in the near future?